Lucid Dreaming: a scientific perspective

A person may come to realize that he or she is dreaming while still in the dream state. References to the phenomenon of lucid dreaming date at least to the time of Aristotle, and have appeared in a variety of contexts, ranging from a letter written in A.D. 415 by St. Augustine, to the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche, and ancient Tibetan Buddhist texts (Gillespie, 1988; LaBerge, 1985). Several works on the subject appeared in the 19th and early 20th century (e.g., (Arnold-Forster, 1921; de Saint-Denys, 1982; van Eeden, 1913). Such dreams were called 'dreams of knowledge' by Oliver Fox (1962) while the German psychologist Paul Tholey who began his studies of consciousness during dreaming in 1959, called the phenomenon 'Klartraum,' literally 'clear dreams' (Tholey, 1983; Tholey, 1989). An overview of the development of lucid dreaming research in Germany by Tholey may be found here. The term 'lucid dream' was introduced by van Eeden in 1913 (van Eeden, 1913).

Frederick van Eeden, who is believed to have first used the term lucid dreaming (van Eeden, 1913)

Of the various definitions of lucid dreaming in the literature, the simplest and most common defines it as a dream in which the individual is aware of dreaming (Green, 1968). Blagrove and Tucker (1994) added the important qualifier that a sleeping subject becomes aware of being in a dream and is able to maintain this awareness without waking up. Other researchers (Hearne, 1981; Hearne, 1987) suggested that dreamers become perfectly or fully aware although the qualifiers 'perfectly' and 'fully' are not explicitly defined. Nonetheless, Blagrove, Hearne and others point to the important correlate of many lucid dreams: the ability to exert a measure of conscious control over dream events. Still, control over dream events is, in itself, not sufficient to indicate a lucid dream (Tart, 1979). LaBerge (LaBerge, 1980) suggested that the consciousness experienced by a lucid dreamer is similar to that experienced during the waking state, e.g., 'the lucid dreamer can reason clearly, remember freely, and act volitionally upon reflection, all while continuing to dream vividly' (p. 1039). Similarly, Tart (1979) suggests that in lucid dreams the 'higher' mental processes typical of waking consciousness, such as the continuity of memory, reasoning, and the volitional control of cognitive processes and bodily actions, are functioning fully. Tholey (1988) and van Eeden (1913) subscribed to similar conceptualizations of the lucid dream state.

These ‘consciousness simulation’ definitions of lucid dreaming are flawed in at least one important respect. While it may be true that the phenomenology of lucid dream experiences resemble those of waking consciousness in general terms, it does not follow that all lucid dream experiences necessarily simulate all features of waking experience, or that all waking state capacities are necessarily available to a dreamer in a lucid state. Rather, a given lucid dream may simulate some waking state capacities while others remain beyond reach. For example, a lucid dreamer may well find him or herself able to appreciate the dream state as a dream (self-reflection capacity), and perhaps also to exercise some control over events within the dream scene, but this appreciation and control may not extend to the ability to remember what day it is (orientation), to what they did just before going to sleep (recent memory), or that they have a meeting the next day (future anticipation). Further, they may be unable to access many other autobiographical memories while lucid. And they their access to logical reasoning may be stifled, as may their ability to intentionally use their imagination or construct a verbal narrative. Many of these cognitive abilities have been documented to appear in lucid dreams, but there is no evidence that they always or inevitably appear all together, or for extended periods of time. Furthermore, these abilities appear in non-lucid dreams with a surprisingly regular frequency (Kahan et al., 1997). For these reasons, we do not conceptualize lucid dreaming as a state in which all waking cognitive capacities are fully available. Rather, the essence of lucid dreaming is the self-reflective capacity to appreciate the dream as a dream; some ability to maintain the state without waking up is also a necessary condition.

The self-reflective capacity of lucid dreaming is a major phenomenological shift in the nature of dreaming that enables the dreamer to access other types of cognitive capacities, but these are best seen as consequences of enhanced self-reflection, and as neither necessary nor sufficient for lucid dreaming to occur. Another possible consequence of becoming lucid within a dream may be an augmentation of the apparent realism of the dream: dream actions, events, objects and characters become amazingly vivid and real, sometimes to the point of surpassing their reality quality of wakefulness (Nielsen, 1991). The apparent realism of dreams may also be a trigger of lucidity within a dream, a feature that forces the dreamer into a state of self-reflection upon the nature of the dream itself. It should be noted, however, that the realism of dreams can be, and often is, augmented without self-reflection or lucidity being provoked. Such changes accompany many common types of dreams, e.g., nightmares, flying dreams, sex dreams, falling dreams, etc. and have been referred to collectively as ‘reality dreams’ (see Nielsen, 1991 for review).

Even the central feature of lucid dreaming, the capacity to reflect upon the fact that one is dreaming, occurs with variable degrees of explicitness or intensity in many dreams. Green (1968, p. 23) identified ‘pre-lucid dreams’ in which the dreamer adopts a critical attitude toward the dream experience, possibly even posing the question 'Am I dreaming?,' but without in fact becoming fully aware that the dream is a dream. She also identified a second type of near-lucid dream in the common ‘false awakening’ which is an experience that one has woken up when in fact it is not the case. Multiple false awakenings may occur within a single sequence, giving the dream a very lucid-like aura but without full lucidity occurring. Other types of dreams approach, but do not quite attain, full lucidity. Many of the reality dream types referred to above (flying dreams, sex dreams, etc.) may bring dreamers just to the verge of an awareness of dreaming and, indeed, this proximity may be one reason that such dreams are often (incorrectly) considered to be lucid dreams. Pre-lucid dreams and false awakenings often occur among lucid dreamers (Blackmore, 1988; Green, 1968; LaBerge, 1985; van Eeden, 1913), as do flying dreams, floating dreams and other reality dream types, but these experiences may be as close as many individuals come to having a truly lucid dream.

Lucid Dreaming in the Sleep Laboratory

Following Aserinsky and Kleitman’s (Aserinsky & Kleitman, 1953) breakthrough discovery that vivid dreams occur most often during periods of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, REM sleep became the focus of intensive scientific investigation. Although it was hoped that the objective study of REM sleep, especially in comparison with non-REM (NREM) sleep, would give rise to a more complete understanding of the dream process, attempts to find specific physiological correlates of dream content yielded very limited results (Pivik, 2000).

LaBerge and colleagues (Laberge et al., 1981a) investigated the possibility that individuals in a lucid dream could signal their awareness by intentionally signaling with their eyes or forearm muscles. This approach proved to be methodologically sound and resulted in several notable experimental findings. Other researchers, such as Keith Hearne of the University of Hull in England and Alan Worsley, a proficient lucid dreamer and subject in Hearne's studies (Hearne, 1983; Hearne, 1982), also investigated lucid dreaming with sleep laboratory tools. Worsley is considered the first individual to have sent a polygraphically observable signal from within a dream (Worsley, 1988).

Some researchers suggested that lucid dreams occurred either during periods of brief awakenings (Schwartz & Lefebvre, 1973) or during NREM sleep (Antrobus & Fisher, 1965). Laboratory evidence, however, supported the position that they take place during REM sleep (Brylowski et al., 1989; Laberge et al., 1981b; Ogilvie et al., ; Ogilvie et al., 1982).

The method of signaling during REM sleep was successfully applied to investigate several features of lucid dreaming. Researchers observed that dreamed patterns of respiration were paralleled by actual patterns of respiration (LaBerge & Dement, 1982b). They observed that dreamed sexual activity was reflected in actual, physiologically measured sexual responses (LaBerge, 1985; LaBerge et al., 1983)). They found that dreamed speech was related to the expiratory phase of the respiration cycle (Fenwick et al., 1984), that dreamed limb movements were reflected in EMG activity (Fenwick et al., 1984), and that dreamed time closely approximated real clock time (LaBerge, 1985). These findings strongly supported the ‘functional equivalence’ position that dreamed actions reflect activity in the same motor, autonomic and emotional systems that subserve such actions in the waking state. Discovery of lesion-induced acting out of dreams (oniric behavior) in cats (Sastre & Jouvet, 1979) and the same phenomenon among human patients with REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD; (Schenck et al., 1986) provided even more convincing evidence for this position.

Physiological activation during lucid dreaming. LaBerge, Levitan and Dement (LaBerge et al., 1986) collected a total of 88 lucid dreams from 7 males and 6 females trained in the MILD technique sleeping in the laboratory. A vast majority of these dreams occurred in REM sleep (94.3%) and there was a large correlation (r=.98, p<.0001) between the probability of having a lucid dream and the serial position of the REM period, i.e., lucid dreams were much more likely later in the night, suggesting a possible influence of a circadian influence (Nielsen, 2010). They also found that physiological measures of sympathetic activation (heart rate, respiration rate, skin potential, REM density) increased significantly 30 sec prior to subjects signaling the lucid dreaming state, and remained elevated for several minutes subsequent to the signals (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Histograms displaying z-scores for physiological measures prior to and following subject signals of lucid dreaming. Signals are aligned with 0 on the x axis. All values are averaged across lucid dreams and subjects. Note activation beginning just prior to signaling and continuing for all measures except skin potential after signaling.

Sex during lucid dreaming: an example. An illustrative example of the signaling method is given by LaBerge, Greenleaf and Kedzierski (1983). The experimental subject, a proficient lucid dreamer, was instructed to perform three eye-movement signals once she found herself in a lucid dream. The first signal was to occur upon becoming lucid, the second at the onset of intentional sexual activity in the dream, and the third when a dreamed orgasm occurred. Sixteen channels of physiological information were recorded including EEG, EOG, EMG, respiration rate, skin conductance levels, heart rate, vaginal EMG, and vaginal pulse amplitude. All of the autonomic physiological measures, with the exception of heart rate, conformed to what would be expected from a subjective report of sexual activity and orgasm.

Singing and counting in lucid dreams. In another experiment (LaBerge & Dement, 1982a), singing and counting, two tasks that typically engage the two brain hemispheres differentially, were investigated. Singing typically results in relatively more engagement of the left hemisphere, as measured by alpha EEG activity, while counting typically results in relatively more engagement of the right hemisphere. Two male and 2 female subjects, (one each right-handed and left-handed) were first monitored during wakefulness while performing singing and counting activities. In the sleep laboratory they were instructed to signal with eye-movements 1) the onset of lucidity, 2) completion of the dreamed singing of a predetermined song, and 3) completion of the task of counting from one to ten. In all cases, the EEG revealed the same patterns of alpha lateralization during the dreamed tasks as had been observed during the waking versions of the tasks.

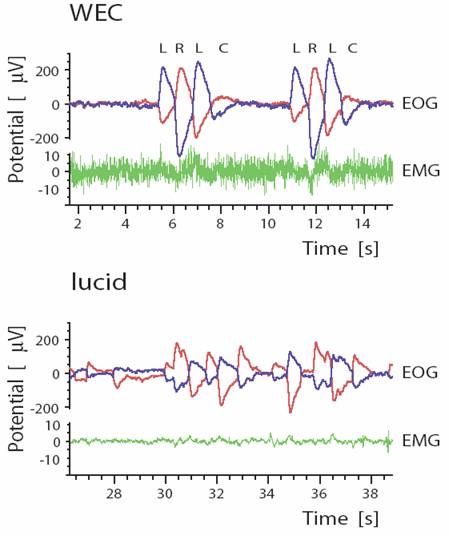

Brain activity during lucid dreaming. A more recent study used a large montage of EEG electrodes to map electrical activity of the brain during lucid dreaming , wakefulness and non-lucid REM sleep (Voss et al., 2009). Of six subjects studied, 3 were able, with encouragement, to produce lucid dreaming episodes and to signal these using a pre-arranged eye movement signal (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Eye movement signal used by experimental subject to communicate to the experimenter during a lucid dream consisted of sets of quick horizontal movements separated by a brief pause. Upper trace (WEC) shows signal during wakefulness as 2 sets of left (L), right (R), left (L), center (C) sequences; lower trace (lucid) shows same signal during a lucid dream. Left and right eye movement electrodes (blue and red lines) are configured such that synchronous movements of the 2 eyes are displayed in opposite directions on the trace; this allows true eye movements to be discerned from muscle artifacts (green channel), which move in the same direction on the eye movement channels (From Voss, et al (2009), Sleep;32:1191-1200, figure 1).

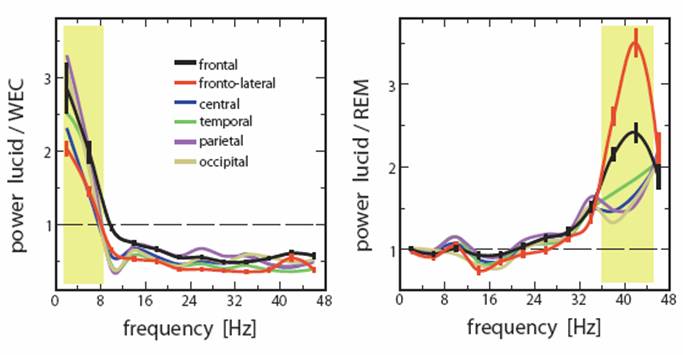

Spectral analysis of 19 EEG placements revealed that lucid dreaming is differentiated from the eyes-closed waking state in displaying greater low frequency (1-8 Hz) EEG power (see Figure 3, left panel) and from non-lucid REM sleep in displaying greater high frequency power, especially near the 40 Hz range (see Figure 3, right panel). The distinctive alpha band (8-12 Hz) activity so characteristic of wakefulness was absent from lucid dreaming, suggesting that lucid dreaming is truly a sleep state, whereas high frequency (gamma) activity was very similar to that of wakefulness. Differences observed were most marked for frontal electrodes. The authors thus concluded that ‘lucidity occurs in a hybrid state with some features of REM (δ[delta] and θ[theta]) and some features of waking (γ[gamma]) and that the frontal and frontolateral regions of the brain play a key role in gaining lucid insight into the dream state and agentive control.’ (p. 1195) [parentheses added].

Figure 3. EEG power for 6 scalp locations during lucid dreaming vs. wakefulness (left panel) and lucid dreaming vs. non-lucid REM sleep (right panel). Yellow shaded areas indicate frequency bands differentiating lucid dreaming from the other 2 states, i.e., increased low frequency power in lucid dreaming vs. wakefulness and increased 40-Hz band activity in lucid dreaming vs. REM sleep (From Voss, et al (2009), Sleep;32:1191-1200, Figure 3).

Frontal lobe activity and lucid dreaming. Neider and colleagues (Neider et al., 2010) examined a possible relationship between lucid dreaming and activity in prefrontal brain regions using tasks known to involve specific frontal regions. A sample of 28 high school students who performed the Wisconsin Card Sort and Iowa Gambling tasks and kept 1-week dream journals revealed an association between greater degrees of lucidity and better performance on the Iowa Gambling Task (see Figure 4) but not on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task, or other characteristics such as self-reported sleep quality prior to or during the study, age, and grade level. The IGT measures affect-guided decision making under conditions of uncertainty whereas the WCST measures mental flexibility and set shifting ability. Further, the brain region engaged by the IGT, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex or VMPFC, is also selectively active during REM sleep (Maquet et al., 2005) whereas the brain region underlying the WCST, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex or DLPFC, is not.

Figure 4. Subject responses to Iowa Gambling Task. Greater lucidity as measured prospectively on the Morning Lucidity Assessment was associated with performance improvement as the task progressed. Statistically significant differences between groups occurred in the 3rd, 4th, and 5th quintiles of trials (From Neider, et al. (2010) Consciousness & Cognition, doi:10.1016/j.concog.2010.08.001).

The authors propose a tentative explanation for the findings: ‘…that the developing capacity for emotion regulation and its integration with cognition, associated with prefrontal cortical development across adolescence (Whittle et al., 2008; Yurgelun-Todd & Killgore, 2006), underlies capacity for both lucid dream induction and affect-guided decision making’ (p. 7).

Clinical Applications of Lucid Dreaming

Anecdotal evidence. Several authors have suggested psychological benefits that may be obtained by spontaneous or intentional lucid dreaming (Kelzer, 1987; LaBerge, 1985; Malumud, 1988; Tholey, 1988). Arnold-Forster (1921) early recounted eliminating her own bad dreams by means of lucid dreaming and suggests that it may be feasible to treat children's nightmares in a similar fashion. Saint-Denys (1982) and LaBerge (1985) also reported personal nightmares in which they became lucid and then positively influenced the course of dream events. Tholey (1988) reported that a lucid dreaming-based program was successful in treating clients with recurrent nightmares as well as clients with symptoms of anxiety, shyness, or social adjustment difficulties. Halliday (1988; 1982) reported two case studies of successful treatment of recurrent nightmares with lucid dreaming; subjects were instructed to become lucid in their nightmares and attempt small changes to the dream scenery. Anecdotal accounts of a similar nature are reported in LaBerge and Rheingold (1990). Brylowski (1990) reported that adding lucid dreaming to therapy of a client with borderline personality disorder and major depression led to reduction of the frequency and intensity of nightmares.

Clinical trials. The Standards of Practice Committee commissioned by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) to develop a Best Practice Guide for the Treatment of Nightmare Disorder in Adults (Aurora et al., 2010) recommends that lucid dreaming therapy (LDT) be considered as a level 3 treatment for nightmare disorder. A level 3 recommendation indicates the opinion that there is at least fair scientific evidence for benefits and puts it on par with other treatments such as hypnosis therapy and self-exposure therapy (Aurora, et al., 2010).

The committee’s recommendation is based on 1 Level 4 study (Zadra & Pihl, 1997) with 5 subjects and 1 Level 3 study (Spoormaker & van den, 2006) with 16 subjects. The former study demonstrated improvement of recurrent nightmares at 1 year when LDT was given to subjects already trained in progressive muscle relaxation and guided imagery. The latter study showed that both 2 hours of individual LDT counseling and 2 hours of group LDT instruction produced statistically significant decreases in nightmare frequency at 12-week follow-up compared with baseline whereas a wait-list control group did not.

The committee did not consider a series of case studies (Spoormaker et al., 2003) in which 8 participants received one-hour individual sessions consisting of lucid dreaming exercises and discussion of possible constructive solutions for their nightmares (a variant of Imagery Rehearsal Therapy for nightmares). Nightmare frequency and sleep quality decreased at 2-mo follow-up, sleep quality increased slighty, but state and trait anxiety did not change.

Lucid Dreaming Induction Techniques

Given that lucid dreaming is a relatively rare spontaneous phenomenon, use of lucid dreaming in either research or clinical contexts requires reliable methods for inducing them. One review (Snyder & Gackenbach, 1988) concluded that somewhat more than 50% of the general population has experienced at least one lucid dream but that only 21% have the experience one or more times a month.

Numerous induction techniques have been suggested in both the scientific and popular literature. The technique of ‘looking at one’s hands’ popularized in the Castaneda series was successfully applied in one research study (Zadra & Pihl, 1997). Another, autosuggestion (Garfield, 1974; de Saint-Denys, 1982; Tholey, 1983), involves repeating to oneself that you will have a lucid dream immediately prior to sleep onset. Garfield (1976) reported increasing the frequency of prolonged lucid dreams from a baseline of zero to a peak 3 per week (p. 183). LaBerge (1980) obtained similar results, reporting an average of 5.4 lucid dreams per month over a 16 month period.

The ‘mnemonic technique for the voluntary induction of lucid dreams’ or MILD technique (LaBerge, 1980, p. 1041) consists of the following steps:

1) awaken spontaneously from an early morning dream;

2) rehearse the dream,

3) engage in 10-15 min of reading or other activity that requires full wakefulness;

4) lie in bed and return to sleep while doing the following:

-repeat ‘Next time I'm dreaming I want to remember I'm dreaming’;

-visualize the body lying asleep in bed with rapid eye movements and in the process of dreaming;

-see yourself being in the dream just rehearsed (or in any other dream, in case none was recalled on awakening) and realizing that you are dreaming;

-repeats the latter steps until the intention is clearly fixed.

Using this procedure over a non-consecutive 6-month period, LaBerge (1980) reports having experienced an average of 21.5 (range: 18 to 26) lucid dreams per month, with as many as 4 in a single night.

Tholey (1983) presents a summary of other induction techniques that were developed following a decade of research involving over 200 subjects. These methods for include the following:

Reflection technique. The subject pays careful attention to his or her environment during the waking state. While examining the surroundings in a critical fashion, he/she asks ‘Is this a dream?’ or ‘Am I dreaming or not?’ The subject should ask this ‘critical question’ as frequently as possible and particularly in situations that resemble some aspect of the subject's own dream experiences. Asking oneself the critical question ‘Am I dreaming or not?’ close to bedtime is considered effective. This technique is based on the assumption (Tholey, 1983, p. 80) that asking such critical questions cultivates a critical-reflective attitude toward momentary states of consciousness while awake that can be transferred to the dream state. The unusual nature of the dream experience can serve as a stimulus the subject can recognize that it is a dream.

Intention technique. The subject resolves to become lucid in a future dream by imagining as vividly as possible that he/she is in a dream situation that would cause him/her to recognize the fact of dreaming. For example, if one frequently dreams of flying, then one should visualize a flying dream while reminding yourself that flying is itself a cue to the fact that you are dreaming. The subject should also resolve to carry out that action in a dream.

Combined techniques. This method combines aspects of intention reflection as follows:

1) ask yourself a critical question (e.g., ‘Am I dreaming or not?") at least five to ten times a day while you;

2) imagine intensely that you are in a dream state, i.e., everything you perceive, including our own body, is a dream and;

3) concentrate on contemporary occurrences in the dream, but also on events that have already taken place. Did you come upon something unusual, or are you suffering from lapses of memory?

Additionally:

4) ask yourself the critical question in all situations that are characteristic for dreams, i.e., whenever something surprising or improbable occurs or whenever you experience strong emotions;

5) use dreams with a recurrent content. If you often feel fear or see dogs in your dreams, then ask the critical question about your state of consciousness whenever you find yourself in threatening situations or you sees a dog when awake;

6) use dream experiences that never or rarely occur when awake, such as floating or flying. When awake, intensely imagine that you are having such an experience, while telling yourself that you are dreaming;

7) employ methods for improving dream recall if necessary;.

8) go to sleep thinking that you will attain awareness of dreaming but avoid any conscious effort of will while thinking this. This method is especially effective after having awakened in the early morning hours and when about to fall asleep again;

9) resolve to carry out a particular action while dreaming; simple motions are sufficient (Tholey, 1983, pp. 81-82).

Other methods for the induction of lucid dreams include the use of external tactile cues (Hearne, 1983) external auditory cues (Laberge et al., 1981c); hypnotherapy (Klippstein, 1988) (click for further information); posthypnotic suggestions (Dane & van de Castle, 1984); techniques for retaining consciousness while falling asleep (LaBerge & Rheingold, 1990; Tholey, 1983) and portable "lucid dream induction" devices referred to as the DreamLight and NovaDreamer (LaBerge & Rheingold, 1990).

Neider and colleagues (2010) used the following procedure for home dream log recording to encourage lucid dreams in their experimental study of lucid dreaming and frontal lobe functions among high school students:

1. I will give you a dream journal in which to write all your dreams for the next 7 days. Keep the journal and a pen within reach of your bed, perhaps on a night table or under your pillow. Every time you wake up from sleep, even in the middle of the night, write down everything that you dreamed as best as you can remember. Sometimes it is difficult to remember things in the beginning but it will get easier. Don’t wait to write your dreams later as this does not work well.

2. Try to go to bed at the same time each night (within an hour). Make sure you have 8 h to sleep each night or more. So if you have to wake up at 6:45 am, make sure you are in bed by 10:45 pm.

3. When you lie down to sleep (both the first time and each time after you wake up at night), spend a minute or two thinking about these things, telling them to yourself:

a. I am going to remember all of my dreams that I dream tonight

b. When I dream, I will know that I am dreaming

c. When I dream, I will be in control of my dreams, able to do what I want to

d. After I dream, I will wake up and write my dreams in my dream journal

4. Don’t forget to write all of your dreams down as soon as you wake up and include descriptions of being aware that you were dreaming and/or being in control of dream if that happened.

Results from the doctoral study by Dane (Dane & van de Castle, 1984) supports the effectiveness of posthypnotic suggestions. Reports by LaBerge and colleagues (LaBerge et al., 1988; Levitan, 1989) suggest that both the MILD technique and the induction devices are effective in increasing the frequency of lucid dreams. Tholey (1983) stipulates that following the induction techniques in his article, subjects who have never experienced lucid dreaming will have one after a median of 4 to 5 weeks.

Online support groups. The internet offers a wealth of social networking sites for the sharing of lucid dreaming-related experiences and induction techniques. Participation in such groups can increase one’s motivation for having lucid dreams, and thus increase their frequency, and are a creative source for ideas about what to do when one is having a lucid dream or how to apply the recall of lucid dreams to one’s daily life. Some recommendations:

Dreamviews.com: this energetic community provides information on the basic stages of sleep, dream recall and how to improve it, lucid dreams and how to induce them, and controlling dreams. Services include forums for sharing dream experiences (of all kinds) but also for organizing and participating in joint lucid dreaming experiments, a site Wiki, DreamTube (featuring videos related to lucid dreaming), and dream journaling software.

REMcloud.com: a social and information network designed to connect people internationally. You can discover other people who had dreams similar to yours, experience global dream trends and themes through the ‘Dream Mosaics’ utility, and follow the dreams of people close to you.

ASDreams.com: The International Association for the Study of Dreams is probably the largest and most respected organization dedicated to supporting those interested in studying and applying dreams (including lucid dreams). It is a non-profit, international, multidisciplinary organization that encourages research, advance uses for dreams, and provides a forum for the eclectic and interdisciplinary exchange of ideas and information. There is an annual conference on dreaming that includes the topic of lucid dreaming (e.g., Kerkrade, The Netherlands, June 24-28, 2011) and many smaller, regional conferences (e.g., Montreal, April 2, 2011).

Lucid Dreaming References

Antrobus, J. S. & Fisher, C. (1965). Discrimination of dreaming and nondreaming sleep. Archives of General Psychiatry, 12, 395-401.

Arnold-Forster, M. (1921). Studies in Dreams. New York: Macmillan.

Aserinsky, E. & Kleitman, N. (1953). Regularly occurring periods of eye motility, and concomitant phenomena during sleep. Science, 118, 273-274.

Aurora, R. N., Zak, R. S., Auerbach, S. H., Casey, K. R., Chowdhuri, S., Karippot, A. et al. (2010). Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 6, 389-401.

Blackmore, S. (1988). A theory of lucid dreams and OBEs. In S.LaBerge & J. Gackenbach (Eds.), Conscious mind, sleeping brain: Perspective on lucid dreaming (pp. 373-389). New York: Plenum Press.

Blagrove, M. & Tucker, M. (1994). Individual differences in locus of control and the reporting of lucid dreaming. Personality and Individual Differences, 16, 981-984.

Brylowski, A. (1990). Nightmares in crisis: clinical applications of lucid dreaming techniques. Psychiatric Journal of the University of Ottawa, 15, 79-84.

Brylowski, A., Levitan, L., & LaBerge, S. (1989). H-reflex suppression and autonomic activation during lucid REM sleep: a case study. Sleep, 12, 374-378.

Dane, J. R. & van de Castle, R. (1984). A comparison of waking instruction and posthypnotic suggestion for lucid dream induction. Association for the Study of Dreams Newsletter, 1(4), 4-8.

de Saint-Denys, H. (1982). Dreams and how to guide them. London: Duckworth.

Fenwick, P., Schatzman, M., Worsley, A., Adams, J., Stone, S., & Baker, A. (1984). Lucid dreaming: correspondence between dreamed and actual events in one subject during REM sleep. Biological Psychology, 18, 243-252.

Fox, O. (1962). Astral projection. New York: University Books.

Garfield, P. (1974). Creative Dreaming. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Garfield, P. L. (1976). Dream content: Does it reflect changes in self-concept? Journal of Sleep Research, 5, 136.

Gillespie, G. (1988). Lucid dreams in Tibetan Buddhism. In S.LaBerge & J. Gackenbach (Eds.), Conscious mind, sleeping brain: Perspectives on lucid dreams (pp. 27-37). New York: Plenum Press.

Green, C. E. (1968). Lucid dreams. Oxford: Institute of Psychophysical Research.

Halliday, G. (1982). Direct alteration of a traumatic nightmare. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 54, 413-414.

Halliday, G. (1988). Lucid dreaming: Using nightmares and sleep-wake confusion. In S.LaBerge & J. Gackenbach (Eds.), Conscious mind, sleeping brain: Perspectives on lucid dreaming (pp. 305-309). New York: Plenum Press.

Hearne, K. M. (1981). A "light-switch phenomenon" in lucid dreams. Journal of Mental Imagery, 5, 97-100.

Hearne, K. M. (1982). Effects of performing certain set tasks in the lucid-dream state. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 54, 259-262.

Hearne, K. M. (1983). Lucid dream induction. Journal of Mental Imagery, 7, 19-23.

Hearne, K. M. (1987). A new perspective on dream imagery. Journal of Mental Imagery, 11, 75-81.

Kahan, T. L., LaBerge, S., Levitan, L., & Zimbardo, P. (1997). Similarities and differences between dreaming and waking cognition: an exploratory study. Consciousness and Cognition, 6, 132-147.

Kelzer, K. (1987). The sun and the shadow. My experiment with lucid dreaming. (2 ed.) Virginia Beach, VA: A.R.E. Press.

Klippstein, H. (1988). Hypnotherapy: a natural method of learning lucid dreaming. Lucidity Letter, 7(2), 79-88.

LaBerge, S. (1980). Lucid dreaming: An exploratory study of consciousness during sleep. Doctoral dissertation, Stanford University. University Microfilms International No. 80-24, 691.

LaBerge, S. (1985). Lucid dreaming. New York: Ballantine.

LaBerge, S. & Dement, W. C. (1982a). Lateralization of alpha activity for dreamed singing and counting during REM sleep. Psychophysiology, 19, 331-332.

LaBerge, S. & Dement, W. C. (1982b). Voluntary control of respiration during REM sleep. Sleep Research, 11, 107.

LaBerge, S., Greenleaf, W., & Kedzierski, B. (1983). Physiological responses to dreamed sexual activity during lucid REM sleep. Psychophysiology, 20, 454-455.

LaBerge, S., Levitan, L., & Dement, W. C. (1986). Lucid dreaming: Physiological correlates of consciousness during REM sleep. Journal of Mind and Behavior, 7, 251-258.

LaBerge, S., Levitan, L., Rich, R., & Dement, W. (1988). Induction of lucid dreaming by light stimulation during REM sleep. Sleep Research, 17, 104.

LaBerge, S. & Rheingold, H. (1990). Exploring the world of lucid dreaming. New York: Ballantine Books.

Laberge, S. P., Nagel, L. E., Dement, W. C., & Zarcone, V. P. (1981a). Lucid dreaming verified by volitional communication during REM sleep. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 52, 727-732.

Laberge, S. P., Nagel, L. E., Taylor, W. B., Dement, W. C., & Zarcone Jr., V. P. (1981b). Psychophysiological correlates of the initiation of lucid dreaming. Sleep Research, 10, 149.

Laberge, S. P., Owens, J., Nagel, L. E., & Dement, W. C. (1981c). "This is a dream": Induction of lucid dreams by verbal suggestion during REM sleep. Sleep Research, 10, 150.

Levitan, L. (1989). A comparison of three methods of lucid dream induction. Nightlight, 1(3), 9-12.

Malumud, J. R. (1988). Learning to become fully lucid: A program for inner growth. In S.LaBerge & J. Gackenbach (Eds.), Conscious mind, sleeping brain: Perspectives on lucid dreaming (pp. 309-318). New York: Plenum Press.

Maquet, P., Ruby, P., Maudoux, A., Albouy, G., Sterpenich, V., Dang-Vu, T. et al. (2005). Human cognition during REM sleep and the activity profile within frontal and parietal cortices: a reappraisal of functional neuroimaging data. Progress in Brain Research, 150, 219-227.

Neider, M., Pace-Schott, E. F., Forselius, E., Pittman, B., & Morgan, P. T. (2010). Lucid dreaming and ventromedial versus dorsolateral prefrontal task performance. Consciousness and Cognition, in press.

Nielsen, T. A. (1991). Reality dreams and their effects on spiritual belief: A revision of animism theory. In J.Gackenbach & A. A. Sheikh (Eds.), Dream images: A call to mental arms (pp. 233-264). Amityville: Baywood Publishing Company, Inc.

Nielsen, T. A. (2010). Ultradian, circadian, and sleep-dependent features of dreaming. In M.Kryger, T. Roth, & W. C. Dement (Eds.), Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine, 5th (5 ed., pp. 576-584). New York: Elsevier.

Ogilvie, R., Hunt, H., Kushniruk, A., & Newman, J. Lucid dreams and the arousal continuum. 4th International Congress of Sleep Research.

Ogilvie, R. D., Hunt, H. T., Tyson, P. D., Lucescu, M. L., & Jeakins, D. B. (1982). Lucid dreaming and alpha activity: a preliminary report. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 55, 795-808.

Pivik, R. T. (2000). Psychophysiology of dreams. In M.H.Kryger, T. Roth, & W. C. Dement (Eds.), Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine (3rd ed., pp. 491-501). Toronto: Saunders.

Sastre, J.-P. & Jouvet, M. (1979). Oneiric behavior in cats [Fre]. Physiology and Behavior, 22, 979-989.

Schenck, C. H., Bundlie, S. R., Ettinger, M. G., & Mahowald, M. W. (1986). Chronic behavioral disorders of human REM sleep: a new category of parasomnia. Sleep, 9, 293-308.

Schwartz, B. A. & Lefebvre, A. (1973). [Conjunction of waking and REM sleep. II. Fragmented REM periods.][Fre]. Revue d'Electroencephalographie et de Neurophysiologie Clinique, 3, 165-176.

Snyder, T. & Gackenbach, J. (1988). Individual differences associated with lucid dreams. In S.LaBerge & J. Gackenbach (Eds.), Conscious mind, sleeping brain: Perspectives on lucid dreaming (pp. 221-263). New York: Plenum Press.

Spoormaker, V. I., van den Bout, J., & Meijer, E. J. G. (2003). Lucid dreaming treatment for nightmares: A series of cases. Dreaming, 13, 181-186.

Spoormaker, V. I. & van den, B. J. (2006). Lucid dreaming treatment for nightmares: a pilot study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 75, 389-394.

Tart, C. T. (1979). From spontaneous event to lucidity: A review of attempts to consciously control nocturnal dreaming. In M.Wolman, M. Ullman, & W. Webb (Eds.), Handbook of dreams: research, theories, and applications (pp. 226-268). New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Tholey, P. (1983). Techniques for inducing and manipulating lucid dreams. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 57, 79-90.

Tholey, P. (1988). A model for lucidity training as a means of self-healing. In S.LaBerge & J. Gackenbach (Eds.), Conscious mind, sleeping brain: Perspectives on lucid dreaming; Part III. Personal accounts and clinical applications (pp. 263-291). New York: Plenum Press.

Tholey, P. (1989). Overview of the development of lucid dream research in Germany. Lucidity Letter, 8(2), 1-30.

van Eeden, F. (1913). A study of dreams. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, 431-461.

Voss, U., Holzmann, R., Tuin, I., & Hobson, J. A. (2009). Lucid dreaming: a state of consciousness with features of both waking and non-lucid dreaming. Sleep, 32, 1191-1200.

Whittle, S., Yap, M. B., Yucel, M., Fornito, A., Simmons, J. G., Barrett, A. et al. (2008). Prefrontal and amygdala volumes are related to adolescents' affective behaviors during parent-adolescent interactions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105, 3652-3657.

Worsley, A. (1988). Personal experiences in lucid dreaming. In S.LaBerge & J. Gackenbach (Eds.), Conscious mind, sleeping brain: Perspectives on lucid dreaming (pp. 321-343). New York: Plenum Press.

Yurgelun-Todd, D. A. & Killgore, W. D. (2006). Fear-related activity in the prefrontal cortex increases with age during adolescence: a preliminary fMRI study. Neuroscience Letters, 406, 194-199.

Zadra, A. L. & Pihl, R. O. (1997). Lucid dreaming as a treatment for recurrent nightmares. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 66, 50-55.